South Kaʻū

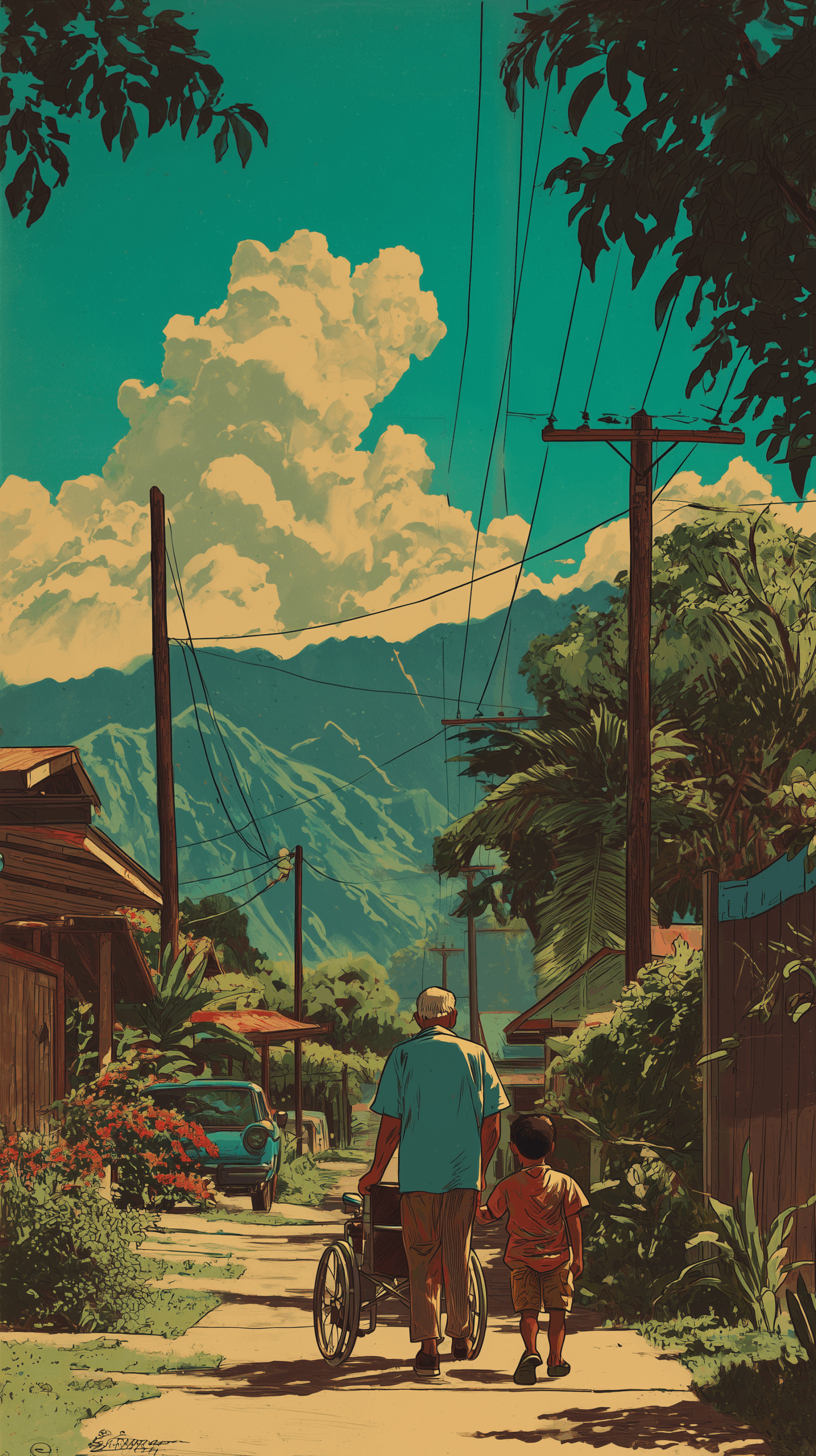

Our community begins where the rain-filled clouds over ever-green hills retreat at the sea of jagged black rocks, where under the grey sky only the mighty ʻōhiʻa lehua, immovable ʻaʻaliʻi, and tenacious ʻuhaloa dare to grow.

We are where miles of black top loneliness lead through a desert larger than neighboring islands with a population smaller than major city blocks. We are off-grid and off-radar, solemn and seemingly forgotten. We are where those seeking escape are found and those seeking existence escape from.

We are a land forged from the fires of Maunaloa, the largest active volcano on Earth, a beacon that brought the first wayfarers to our rocky shores – the first Native Hawaiians. Life has always been difficult here and those who remained, earned renown for their resilience – they were given epithets spanning ages: Kaʻū mākaha – Kaʻū of the fierce fighters; Kaʻū malo ʻeka, kua wehi – Kaʻū of the dirty loincloth and black back.

Perhaps it was our own grit that made us an appropriate heir to the expertise of the vaqueros and under their guidance, our paniolo (Hawaiian cowboy) culture was born when beef was big in the 1880s. Rodeos are still big around these parts and many of our families still cling to their cowboy ways.

The turn of the 20th Century brought western settler colonialism and gifted the fierce fighters economic hardship. As the black backs sought shade and opportunity in the urban core, there were none left to tend to the māla. The farms that once fed communities went fallow – the land slept as our ancestors wept for their departing children.

There were the land-grabs of the 1980s, where devious developers capitalized off of fledgling land laws and fleeing families, converting tens of thousands of acres of lava desert into sprawling subdivision grids marketed to unsuspecting foreigners as their chance to buy a piece of paradise.

Many tried to carve a life from this sharp and unforgiving stone, but most never make it. Some have no choice. Those of us with deep enough roots are lucky enough to hold on much stronger than the rest. But, there’s only so much we can hold and for those of us who have forgotten why are our roots run so deep, we don’t seem to possess the will to hold on for much longer.

Today, Native Hawaiian descendants of the first people to set foot in these islands share this land with non-Native settlers. We’re an eclectic mix of people, the impoverished living next door to short-term vacation rentals serving as income-generating assets to millionaires. Like the countless flows of lava that made our community, our identity flows in rivers of fire; some are lost to the sea, while others fortify the land, creating more.

This is Hawaiian history passing right before us – how Native Hawaiian identity was lost to the sea. However, we can (and should) learn from the past and we have the means to alter the course of this repeated history. We need to stop the pattern of forced Native Hawaiian outmigration, which leaves our ancestral lands void of our presence – our absence leaves our sacred sites and natural-cultural resources unprotected and vulnerable to desecration and destruction. To keep us here, in our homeland, we need the space to grow and more importantly, we need to remember why this place was so special to begin with.

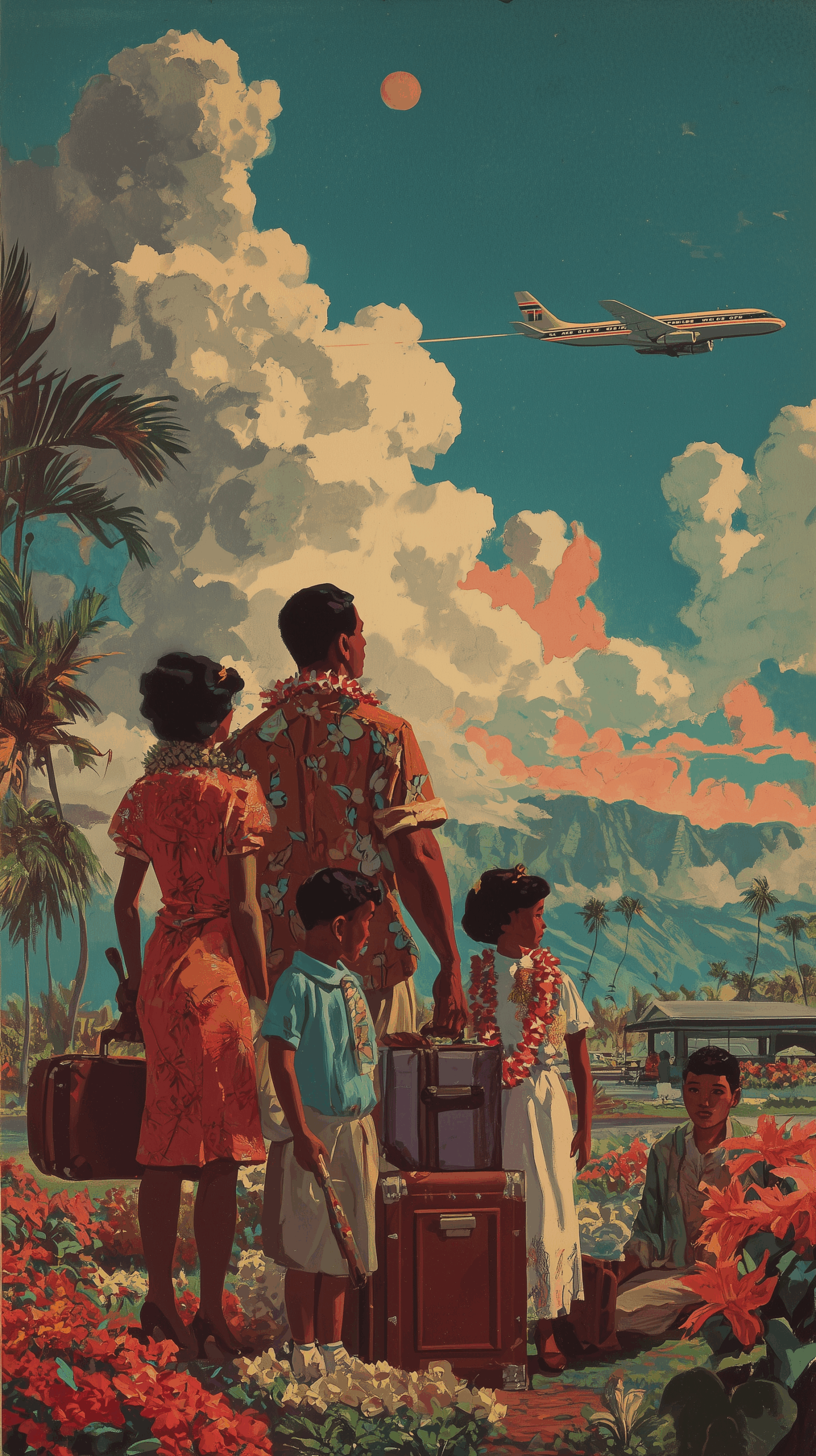

Native Hawaiian Outmigration

Native Hawaiian outmigration refers to the growing trend of Native Hawaiians leaving the islands, often relocating to the continental U.S. in search of affordable housing, better job opportunities, and improved quality of life. Today, nearly half of all people of Native Hawaiian ancestry live outside Hawai‘i, a shift driven largely by Hawai‘i’s skyrocketing cost of living, lack of affordable housing, and a limited local economy that too often fails to support Native families. This outmigration is more than just a demographic concern — it represents a cultural (and identity) crisis.

As Native Hawaiians are displaced from their ancestral lands, the intergenerational transmission of language, traditions, and cultural knowledge is disrupted. The migration not only weakens the social fabric of Native Hawaiian communities but also diminishes their political representation and influence within their homeland. The result is a deepening disconnection between people and place, threatening the cultural survival and self-determination of the Native Hawaiian people.

| Topic | Insight |

|---|---|

| Population Off-Island | Nearly 50% reside outside Hawai‘i. |

| Current Outmigration Rate | Native Hawaiians vulnerable to forced outmigration. |

| Drivers | Education, economic opportunity, housing costs cited in multiple studies. |

| Public Sentiment | Over one-third are contemplating yet to leave—reflecting future risk. |

| Historical Context | Cultural migrations historically, intensified in post-statehood and modern economic pressures. |

- Impact 1: Cultural Displacement

- Impact 2: Weakened Community Bonds

- Impact 3: Brain Drain & Economic Leakage

- Impact 4: Erosion of Land Stewardship

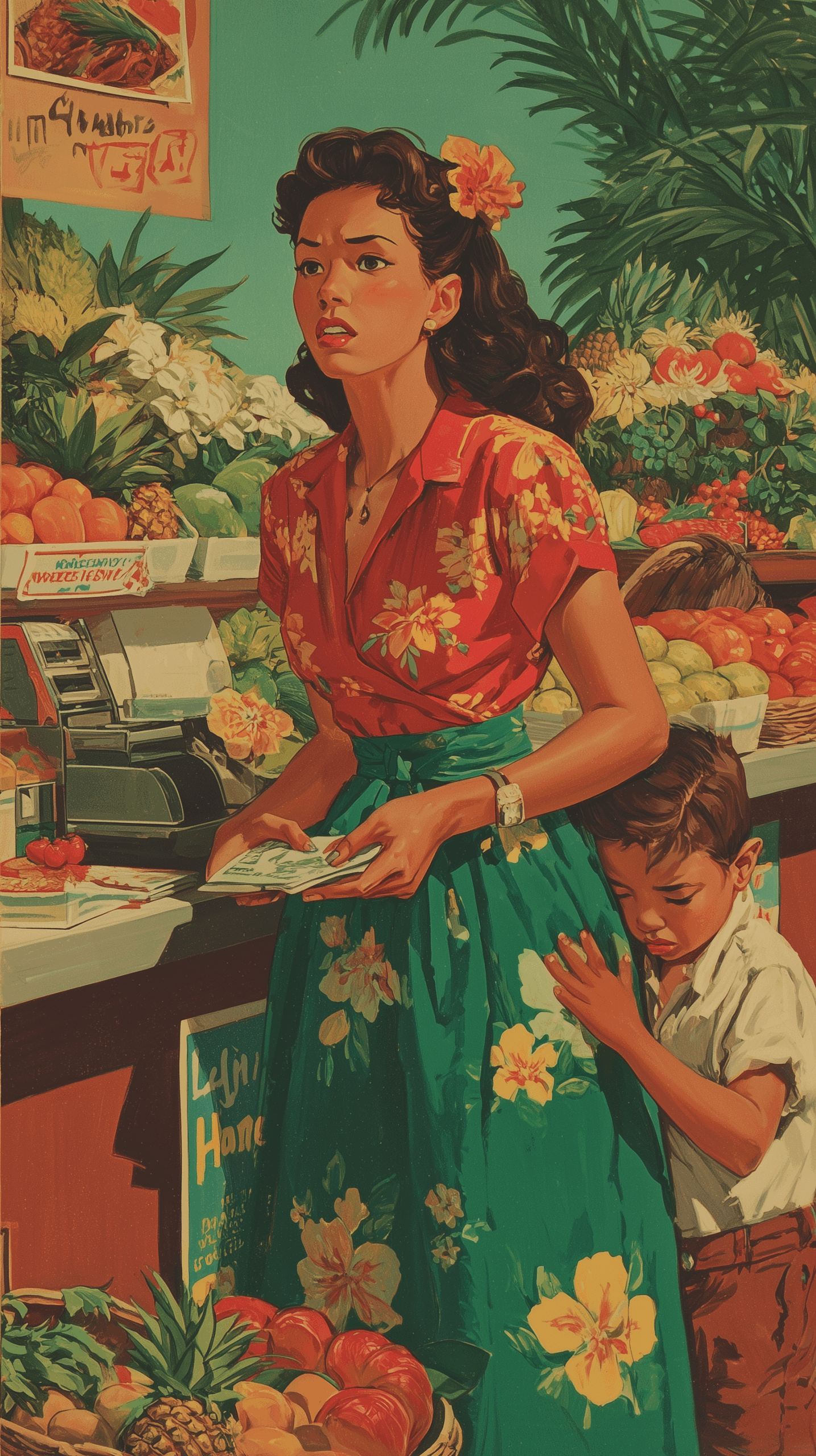

Income Disparity

Income disparities affecting Native Hawaiians and rural communities like Kaʻū reflect deep-rooted structural inequalities that limit opportunity and economic mobility. Native Hawaiians consistently earn less than the state average, with median household incomes thousands of dollars below their non-Hawaiian counterparts. These income gaps are compounded by lower rates of educational attainment, systemic barriers to high-paying jobs, and the dominance of low-wage industries like tourism and service work.

In Kaʻū, and specifically in Ocean View (South Kaʻū), income disparities are even more severe. Median household income in Ocean View is less than half the state average, with high poverty rates and limited access to local employment, education, and basic services. Residents often endure long commutes, economic isolation, and inadequate infrastructure. For Native Hawaiian families in these rural areas, the consequences of income disparity are not just financial—they erode cultural resilience, community well-being, and the ability to remain rooted in ancestral homelands.

| Topic | Insight |

|---|---|

| Native Hawaiian Median Income | Native Hawaiians earn significantly less than the statewide average (~$72,762 vs. ~$80,316), with persistent income gaps across decades. |

| Poverty Rates | Over 13% of Native Hawaiians live in poverty nationally—more than double the rate for non-Hispanic whites. In rural areas like Kaʻū, poverty exceeds 16%. |

| Education & Economic Mobility | Only ~20% of Native Hawaiians hold a bachelor’s degree (vs. ~40% of white residents), limiting access to higher-paying jobs. Ocean View’s rate is even lower at 15.2%. |

| Cost of Living vs. Wages | High housing and living costs across Hawai‘i outpace wages—especially in low-wage sectors like tourism—trapping families in paycheck-to-paycheck cycles. |

| Rural Isolation | Ocean View residents face long commutes (average ~70 minutes), few local jobs, and limited access to services—worsening economic exclusion and opportunity gaps. |

- Impact 1: Housing Insecurity and Displacement

- Impact 2: Limited Access to Quality Education

- Impact 3: Health Inequities

- Impact 4: Weakened Cultural Continuity

- Impact 5: Reduced Civic and Political Influence

Health Disparity

Native Hawaiian and rural health disparities reflect a deep imbalance in access, outcomes, and culturally appropriate care. Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders experience higher rates of chronic illnesses—such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and obesity—than any other major ethnic group in Hawai‘i, and they have the lowest life expectancy in the state.

These disparities are intensified in rural areas like Kaʻū, where healthcare infrastructure is severely limited, with long travel distances, few medical providers, and inadequate emergency and specialist services. Residents in these communities report more frequent days of poor physical and mental health, and often lack the resources or support to manage chronic conditions. Compounding the issue is the marginalization of traditional Native healing practices like lā‘au lapa‘au and midwifery, which are frequently overlooked or restricted by Western medical systems. These systemic gaps not only worsen health outcomes but also erode trust, cultural continuity, and overall community resilience.

| Topic | Insight |

|---|---|

| Chronic Disease Burden | Native Hawaiians experience disproportionately high rates of heart disease, diabetes, cancer, obesity, and other chronic illnesses, often beginning at earlier ages than other groups in Hawaiʻi. |

| Life Expectancy Gaps | Native Hawaiians have the lowest life expectancy of all major ethnic groups in the state, often dying 6–10 years earlier than non-Hispanic whites. |

| Access in Rural Areas | Rural communities like Kaʻū face critical shortages of healthcare providers, long travel times to clinics, and limited access to specialists, emergency care, and preventive services. |

| I/DD Disparities | Roughly 11% of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander children have intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). Rural families face even greater challenges accessing early diagnosis, behavioral supports, and culturally responsive, coordinated care. |

| Cultural Disconnection | Traditional Native Hawaiian healing practices (like lā‘au lapa‘au and midwifery) are often excluded from formal health systems, limiting culturally grounded care and eroding trust in Western medical institutions. |

| Mental Health & Health Quality | Native Hawaiian and rural residents report significantly more days per month of poor physical and mental health, reflecting higher stress, chronic conditions, and limited access to mental health services. |

- Impact 1: Higher Rates of Chronic Illness & Early Mortality

- Impact 2: Limited Access to Healthcare Services

- Impact 3: Declining Mental Health and Community Well-Being

- Impact 4: Inadequate Support for Individuals with I/DD

- Impact 5: Undermining of Traditional Healing and Cultural Practices